Introduction

“Teaching the Middle East after the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions…Beyond Orientalism, Islamophobia, and Neoliberalism,” a conference sponsored by the Middle East Studies Program and the Ali Vural Ak Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University, and by the Arab Studies Institute (which includes Arab Studies Journal and Jadaliyya), brought together forty participants for an intense conversation on 13-14-May 2011 at George Mason University regarding the future of pedagogy and scholarship dealing with the region (see List of Participants and Abstracts below).

The invited participants represented a wide range of disciplines and approaches, and the discussions brought together scholars whose work has been central to the development of the field with new voices whose work has emerged in recent years, in order to address the question: What sorts of teaching and research agendas do we need to establish in order to address the histories and emerging realities of the region? The ensuing conversations helped to lay the foundations for the ongoing work of elaborating, critiquing, and beginning to realize these pedagogical and scholarly agendas.

[Panel on "Reframing Research Agendas and Analytical Narratives. Left to right: Cemil Aydin, Pete Moore, James Gelvin, Zachary Lockman, Nadya Sbaiti, Rabab Abdulhadi, Hesham Sallam]

[Panel on "Reframing Research Agendas and Analytical Narratives. Left to right: Cemil Aydin, Pete Moore, James Gelvin, Zachary Lockman, Nadya Sbaiti, Rabab Abdulhadi, Hesham Sallam]

Given the timing of the conference in the midst of the still-ongoing Arab Spring, the events of recent months, including the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt and the continuing popular uprisings throughout the region, were front and center in these discussions. However, the deeper rationale behind the conference goes further back. The full raison d’etre for the conference was set out by Bassam Haddad during his opening remarks. As he noted, during the past decade, we have witnessed an important theoretical questioning of the dominant conceptual tools used to analyze the social, political, and cultural lives of Middle Eastern societies. The moment of the Arab Spring, taken together with this ongoing questioning process, presents itself, Haddad suggested, as a particular opportunity to switch pedagogic and scholarly modes and strategies from "defensive" to "non-defensive" ones across the board. Traditionally, many educators have found themselves forced to teach the Middle East in defensive ways that were consumed by reacting to dominant but reductionist world-views and paradigms, especially at the undergraduate level. A glance at the state of mainstream discourse regarding the region, whether in terms of media coverage or policymaking, reveals both the poverty and the power of these dominant paradigms; students, even those with an interest in the region, are of course deeply influenced by these paradigms before they ever reach the classroom. This fact has been exacerbated by the fact that specialists in the field of Middle East Studies who come from different disciplinary backgrounds have not always been able to find ways to speak across these disciplinary differences; the attempt to foster this conversation was, as Haddad noted, another of the important motivations behind the conference.

Some of the most important intellectual developments in the analysis of the region have emerged as ways of disputing and disrupting certain dominant narratives, including approaches founded in critiques of Orientalism, Islamophobia, and neoliberalism. These approaches continue to provide crucial tools, but as Haddad noted in his remarks, the opportunity to move away from defensive modes of reaction, and towards new sorts of non-defensive scholarly and pedagogical strategies, has begun to emerge. Needless to say, the recent revolts and revolutions in the region have sped up this process, and have opened the door for a fundamental rethinking of the methodologies and paradigms used to understand the Middle East. Empirically, we are witnessing a rare teachable moment, when so much of what many educators have been working to debunk in the classroom is being debunked before our eyes in the region. But, as Haddad pointed out, this does not mean that what we are seeing and experiencing is necessarily an automatic teachable moment; what we need, in other words, are pedagogical and research strategies designed to help seize the moment and work towards larger sorts of transformations in the teaching of the Middle East.

Meanwhile, even denizens of the mainstream media and of policymaking, who have traditionally been hostile to those voices that have challenged the dominant paradigms for thinking about the region, have begun to pay heed to some of these same voices to explain the popular uprisings of the Arab Spring — events which their usual stable of “experts,” steeped in the narratives of Orientalism, Islamophobia, and neoliberalism, had declared to be impossible. Indeed, one of the most important sets of discussions that emerged at the conference focused on the role of the intellectual in the wake of these developments, and where educators and scholars should best aim their voices today: Should the goal be to try to influence policymakers in Washington and other traditional centers of power? Should it be to try to intervene in and change the way the media covers the region? Should it be to find other ways to reach larger audiences, including students, in a way no longer focused on simply reacting to and countering the dominant narrative, but based instead on helping this larger audience to become aware of new modes of thinking about the region?

As the panel reports and abstracts show, these and other crucial questions were raised and addressed throughout the conference; the closing discussion sessions in turn added new questions that will be addressed in the ongoing work to come. Through the discussions, panelists moved productively between addressing current events (with frequent reminders both of the urgency of findings modes of analysis for these events, but also the humility necessary for doing justice to their evolving and fast-changing nature) and thinking through larger questions of methodology. Questions emerging from the ongoing popular uprisings — for example, whether the term “revolution” is an accurate one to describe what has happened in Tunisia and Egypt — sent participants back to issues of methodology, such as the question of how to formulate new modes of comparative study of revolutions. On the other hand, methodological questions, such as the tension between modes of analysis grounded in political economy and those related to discourse analysis, came to be considered and tested not as abstract disciplinary questions, but rather in terms of what they might help us to understand about recent events, and how they might provide useful frameworks for future inquiries.

[Presentation by Khalid Medani. Left to right: Linda Herrera, Toby Jones, Khalid Medani, Ziad Abu-Rish]

[Presentation by Khalid Medani. Left to right: Linda Herrera, Toby Jones, Khalid Medani, Ziad Abu-Rish]

What follows are a series of summaries of the panels that made up the conference. The first six panels featured a series of presentations followed by a discussion period. The final two panels were designed entirely as discussions, meant both to provide a conclusion to the conference and also to set the agenda for the ongoing discussion that will follow; the first concluding panel focused on setting research agendas, and the second on setting agendas for pedagogical approaches and teaching strategies. Each panel summary includes links to comprehensive abstracts of each individual presentation; these abstracts can be found in the Pedagogy section of Jadaliyya.

One of the motivations behind this conference was the understanding that the attempt to switch modes from a defensive to a non-defensive approach, and the effort to develop new pedagogical and research agendas in order to address the events of the Arab Spring and beyond, will require institutional backing, networking, collaboration, and innovation. This conference was conceived in hopes of contributing to this goal, and the ongoing work that comes out of the discussions begun at the conference will proceed with this same goal in mind. The Jadaliyya Pedagogy page will be one place where this work will go forward, so we hope that you’ll all join us for the discussion there.

We at Jadaliyya, along with Arab Studies Journal, would like to extend our sincere appreciation to the Ali Vurak Ak Center for Global Islamic Studies and the Middle East Program, both at George Mason University, without who`s financial and logistical support, the conference would not have been possible.

Panel Summaries

Panel 1: Focus on Egypt

The conference panels were kicked off by a panel that used Egypt as a case-study, both in terms of understanding the dynamics of one particular uprising as well as thinking specifically about the pedagogical implications of that uprising on the teaching of Egyptian history and contemporary politics. Joel Beinin, in his presentation entitled "Workers and Egypt’s January 25th Revolution: Shifting the Discussion from Autocracy/Democracy to Political Economy and Equity," argued that a political economy approach is vital to understanding and talking about events that have been described as "the Egyptian revolution." For Beinin, the most significant dimension of opposition to the regime relates to the predations of Egyptian neoliberalism, one of the major milestones of which was the creation of a "government of businessmen" in July 2004. Opposition to neoliberal policies were an important center of pre-January 25 mobilizations as Egypt`s poor and working class have come to spend approximately eighty percent of their disposable income for food and other basic needs. Such dynamics spurred a steady rise in collective actions (protests, strikes, sit-ins, etc.) which formed an essential component of the repertoires drawn on after January 25th.

[Joel Beinin]

Jason Brownlee, in his presentation entitled "How the January 25th Uprising Is Reshaping the Norms of Egyptian Domestic and Foreign Policy,” offered a form of conceptualizing contemporary Egyptian politics that moves beyond the unsatisfactory regime-centered elitist analysis that dominated before January 25th. The alternative "pluralistic" model is made up of the following components: traditional elites connected to the ancien regime and the business community; electoral politics, which is dominated by a combination of religious conservatives and political entrepreneurs; and street politics, the Egyptians who go into the streets and participate in contentious politics. Such a framework, Brownlee argued, helps makes sense of dynamics such as the "asymmetric success" of liberal and leftist groups/constituencies, wherein they dominate public protests but have been unable to achieve more institutional forms of power and influence.

[Jason Brownlee]

Paul Sedra, in his presentation entitled "Egyptian History without Egypt? Privileging Pluralism in a Post-Revolution Pedagogy," took as his point of departure the powerful images of Muslims and Christians protecting each other during prayers in Tahrir Square. He highlighted the ways in which "national unity" is an ill fit for these cross-sectarian solidarities, especially in the light of the long (and regime-sponsored) discourse of "national unity." Sedra was critical of the tendency of scholarly attention to focus on the Coptic community only when the latter attracts Islamist attention. At the heart of his presentation, Sedra explored whether Egyptian nationalism (and studies of it) can accommodate a distinctly Coptic political culture.

[Paul Sedra]

Paul Amar`s presentation, "How the Egyptian Revolution Teaches Political Sociology, Global Political Economy, Gender Studies, and Geopolitics," highlighted how the uprising has generated new images and narratives about Egyptians, Egypt, and the Middle East, thus providing a refreshing departure from — and repudiations of — exotic and terrorlogical semiotics. However, Amar attempted to push this further by advocating the positioning of Egypt (and the Middle East) as a point of "futurity," both regionally and globally, as contrasted with the backward-looking narratives that dominate academic discourse. He was particularly interested in exploring the ways in which Tahrir-modeled experiments in labor organizing are being implemented elsewhere in the region, as well as in the United States.

[Left to right: Joel Beinin, Paul Amar, Paul Sedra]

Peter Gran`s presentation, "Thoughts Out of Season," highlighted some of the more structural constraints facing undergraduate education. He began by stating that people who shape public opinion in the media shape student perspectives, which the latter bring into the classroom. Gran believes it is somewhat premature to draw conclusions about the transformations since January 25th, and instead suggested scholars not shy away from understanding the nature of, and strategizing about how to dismantle, the deeper structure at play in the minds of both students and colleagues.

[Peter Gran]

Panel 2: Knowledge Production and the Role of the Academic

The second panel sought to link knowledge production to social change and critically consider the role of the academic in the classroom and beyond. In "Producing Knowledge for Justice? Gender and Sexuality Studies and the Consumption of Arabs and Muslims," Rabab Abdulhadi tackled the issue of knowledge production and its potential relationship to the advancement of justice. She posed and discussed the question of whether the urgency of change in researching the Middle East, which has been expressed by some in the wake of the Arab uprisings, reflects a similar urgency in terms of classroom teaching. Abdulhadi went on to explore this question by highlighting the ways in which the Arab uprising provides a teaching moment about both our individual areas of expertise as well one about our students and their locality (i.e., also a teaching moment about American-ness).

[Left to right: Nadine Naber, Anthony Alessandrini, Shiva Balaghi, Rabab Abdulhadi]

In "De-Orientalizing Pedagogy," Nadine Naber highlighted the ways in which Arab-American Studies is trapped between Orientalist and anti-Orientalist discourses. Accordingly, dominant trends tend to be shaped by long-distance nationalism, focusing so much on institutional power and government policies that human beings as subjects and agents disappear. Naber stressed the use of gender and queer theory to respond to this dilemma and to work our way out of an anti-Orientalist defensive posture that critiques government practices at the expense of critical and necessary discussion about agency.

[Nadine Naber]

Stephen Sheehi, in "The Social Relations in Islamophobia and the Role of the Academic," addressed both the issue of Islamophobia and the role of the educator. He argued that we need to view Islamophobia as an ideological formation that is historical in nature, deployed to perpetuate American empire. He stressed that the role of Middle East scholars as experts must include imagining themselves as transformative intellectuals and not simply scholars. In this sense, the call for critically interrogating Islamophobia is at once a call for critically interrogating our roles in educational institutions as part of a broader society implicated in empire, and a call for resistance to it.

[Left to right: Shiva Balaghi, Rabab Abdulhadi, Stephen Sheehi, Bassam Haddad]

Anthony Alessandrini`s presentation, "Pedagogical Uprisings: Teaching to the Unconverted, or Against Multiculturalism`s Middle East," addressed the issue of institutional multiculturalism and the ways it has become a mechanism for diversity management. He challenged the one-of-each-text model for teaching world literature or regional literature, linking this dilemma to broader questions of solidarity that go beyond merely expressing it to practicing it in the classroom.

[Left to right: Anthony Alessandrini, Shiva Balaghi, Rabab Abdulhadi, Stephen Sheehi]

Day 1 Lunchtime Talk by Nir Rosen

Between the second and third panels, Nir Rosen presented a lunchtime talk, "A Critique of Reporting on the Middle East." A version of his talk can be found here.

[Nir Rosen]

Panel 3: Reframing Analytical Narratives and Research Agendas

This panel sought to evaluate the ways in which the Arab uprisings give pause to the assumptions undergirding both teaching frameworks as well as research agendas. Cemil Aydin`s "Rescuing the History of Universalism and Modernity from the Eurocentric Decline Paradigm" highlighted the ways in which problematic coverage of the Arab uprisings is linked to previously dominant trends in Middle East historiography. Part of this, he argued, is to be found in Eurocentric understandings of history where global values such as liberty and democracy are traced back to modern Europe. Aydin also argued that this is related to larger organicist civilizational discourse of the decline of the East and the rise of the West. Another part of this paradigm is the persistent misconception of an alleged misfit between Muslims and secularism.

[Left to right: Cemil Aydin, James Gelvin, Zachary Lockman, Nadya Sbaiti]

In her presentation, “Disoriented: Rethinking Middle East, Far West, and the Points in Between,” Nadya Sbaitiprovided examples of how hard it is to teach Middle East survey courses and be satisfied with what students take away in the end. One of these take-aways, according to Sbaiti, invariably ends up being the understanding that the West acts and the East reacts. This occurs almost irrespective of how syllabi are organized (chronologically, thematically, etc.). Despite all attempts to complicate historical narratives, the West in one way or another emerges as the point of reference. For Sbaiti, the opportunity presented by the revolutions is to rethink what exactly constitutes a historical event, moving away from the interactions with the West as exclusively defining moments.

[Left to right: Zachary Lockman, Nadya Sbaiti, Rabab Abdulhadi]

Pete Moore`s "Back to Basics in Political Economy: Power and Inequality" argued that the Arab uprisings are an opportunity to get back to basics: power and inequality. He probed which political economy frameworks can help understand uprisings within these two related concepts, and drew on Karl Polanyi`s notion of the free market as "alien to human society" to make some interjections about the dynamics underlying the uprisings and what led up to them.

[Pete Moore]

In "Rethinking the Big Picture: Narrative Middle Eastern History in the Wake of the Arab Uprisings, 1944-Present," James Gelvin highlighted the challenge of creating a framework to make sense of post-World War II history beyond simply listing a sequence of events. He discussed various iterations, but arrived at one where a "civic order" comes into place a result of a confluence of factors, such that various events can be understood as struggles around/within that civic order. This, he argues, allows for the incorporation of three thematic discussions that can be related but are also independent spheres of inquiry: authoritarian state building; U.S. policy; and resistance to local and external forces.

[Left to right: Pete Moore, James Gelvin, Zachary Lockman]

Hesham Sallam`s "Challenges and Tradeoffs in Moving Beyond Dominant Approaches to the Study of the Comparative Politics of the Middle East" identified tough challenges to move beyond a defensive mode of teaching. In political science courses, Sallam argued, we tend to take cues from theories that stand on shaky ground. By the time an instructor is finished demolishing problematic theories, the semester is over, and consequently the instructor and students have spent more time talking about what Middle East politics is not, and less about what Middle East politics actually is.

[Hesham Sallam]

In "Making Connections," Zachary Lockman reminded us that students do not come to class as blank slates. Thus, for him, the first task of a course is that it help students to adopt a critical attitude. Lockman argued that it is worth thinking about intersections we can exploit usefully, between what happens in the Middle East (initially distant and unknown) and students` own lives (in the United States). He highlighted how the lives of our students are shaped by the same neoliberal agenda that is shaping the lives of the people in the Middle East, and thus the ways in which it makes sense to critically locate them (all of us) in the same social time and space.

[Zachary Lockman]

Panel 4: Bringing the Middle East into the Fields of Law and Theory

The fourth panel of the conference sought to consider the ways in which the teaching of law in the Middle East has been affected by the Arab uprisings, as well as the relationship of the Arab world to this broader project, both political and academic. Noura Erakat, in "Problematics of Teaching International Law in the Contemporary Middle East," drew attention to how the Arab uprisings have facilitated the teaching of international law and human rights in the Middle East, specifically in that claims made by people were less claims exclusively vis-à-vis their state and more claims of human dignity vis-à-vis broader notions of rights. For Erakat, scenes of regimes deploying military force against unarmed protesters have complicated, though not eliminated, the exceptionality of Israel`s violence vis-à-vis discussions of international law. In this sense, authoritarian regimes and occupying regimes resort to the same type of violence, and this recently displayed symmetry has forced some to question what otherwise was a discourse that was permissive of Israel`s actions.

[Left to right: Sumaiya Hamdani, Agnieszka Paczynska, Lisa Hajjar, Noura Erakat]

In "Following the Torture Trail from Middle East Studies to American Studies," Lisa Hajjar pointed out the centrality of torture in the way we think about the Arab uprisings, authoritarian regimes, and the United States. For her, the practice of torture says something significant about the nature of the regime, and we have to understand that there is no such thing as a liberal torturing state. To torture, for Hajjar, is by definition to be illiberal.

[Left to right: Agnieszka Paczynska, Nadine Naber, Lisa Hajjar]

Agnieszka Paczynska, in "Teaching the Middle East in Theory Courses," provided examples of the ways in which the Arab uprisings offer an opportunity for students in interdisciplinary and cross-regional studies to think of the Middle East through lenses other than those of Islam or oil.

[Left to right: Sumaiya Hamdani, Nadine Naber, Agnieszka Paczynska, Lisa Hajjar]

In "Who`s Afraid of Iran? Neocons` Enduring Influence on US Policy Analysis," Shiva Balaghi highlighted the persistence of the "Iran Question" in the face of developments in the Arab world in U.S. policy circles. She argued that the issues of Arab nationalisms, as well as secular opposition movements, have been removed from the equation in favor of a broader notion of a Sunni vs. Shia struggle. Within context of Neo-Conservatives’ advocacy of war on Iran, for Balaghi, the question that keeps presenting itself is who will attack Iran, as opposed to whether Iran will be attacked.

[Left to right: Shiva Balaghi, Nadine Naber, Agnieszka Paczynska, Noura Erakat]

In "Teaching Islam after the Revolution," Sumaiya Hamdani discussed pedagogical approaches to teaching courses dealing with Islam in the contemporary context, as well as the sorts of challenges traditionally to be found in teaching this topic. Among the questions she raised were how to teach students to regard the "soundtrack" of the recent revolutions: for example, how to understand the role of Friday prayers, which have often been followed by protests with an avowedly secular underpinning, or how to think about images of prayer in the protests as part of larger multiconfessional actions and movements. Hamdani also discussed approaches to teaching the history of Islam without separating the past from the present and thus turning the past into "a foreign country."

[Left to right: Sumaiya Hamdani, Nadine Naber, Agnieszka Paczynska, Lisa Hajjar, Noura Erakat]

Panel 4: Peripheries and Exceptions

The second day of the conference began with a panel that focused on states and issues that have been marginal to the dominant discourses about the Arab uprisings. However, the goal of the panel itself was to highlight the actual centrality of these issues to a deeper understating of these uprisings and their consequences for teaching the Middle East. Asli Bali, in her “Comparative and International Law of the Middle East After the Uprisings: Re-assessing the State of the Arab State,” highlighted the ways in which “law” is exceptionalized in Middle East studies and, in turn, how the Middle East is viewed as exceptional in legal studies. For her, there are three conceptual problems with the ways in which the Middle East is presented in legal studies (i.e., law schools): a lack of a regional paradigm for discussing law in the Middle East; the relevance of the Middle East within legal studies is restricted to questions of cultural relativism (i.e., Islam); the assumption that civil society is dormant and thus no domestic grassroots pressure in the region for human rights. Bali argued that the current uprisings challenge these conceptions and should be used to challenge their dominance. She concluded her presentation by highlighting the problematics the ways in which US law schools are engaged in shaping political outcomes for contexts they know little about, pointing to how academics and students were directly engaged the writing of the Iraqi constitution and how current students are being trained to write constitutions for other countries: possibly Egypt but certainly Bahrain.

[Left to right: Joel Beinin, Asli Bali, Linda Herrera, Toby Jones, Khalid Medani, Ziad Abu-Rish, Maya Mikdashi]

In “Youth and Citizenship in a Digital Age,” Linda Herrera advanced the argument that in these discussions, we should not forget about the generational dimensions, specifically the dimension of youth. She highlighted the issue of culture and politics of schooling and questions both the emancipatory possibilities of different types of education as well as their functions as systems of control. For Herrera, an engagement with these questions forces one to consider two dynamics: the privatized/neoliberal education model and out-of-school learning via new communication technology and social media.

[Linda Herrera]

In “Democracy and its Limits in the Persian Gulf,” Toby Jones argued that while the outcomes of events in the Persian Gulf are still in the balance, the actions there are not peripheral to the region but at the very heart of the new trends towards counter-revolution in the region. He called for greater attention to this counter-revolution by looking at centers of power in the region and questioning what mobilizes regimes for counter-revolutionary violence. For Jones, developments in Bahrain speak to the heart of attempts to preserve the regional political and economic order on the part of Saudi Arabia and the United States.

[Left to right: Linda Herrera and Toby Jones]

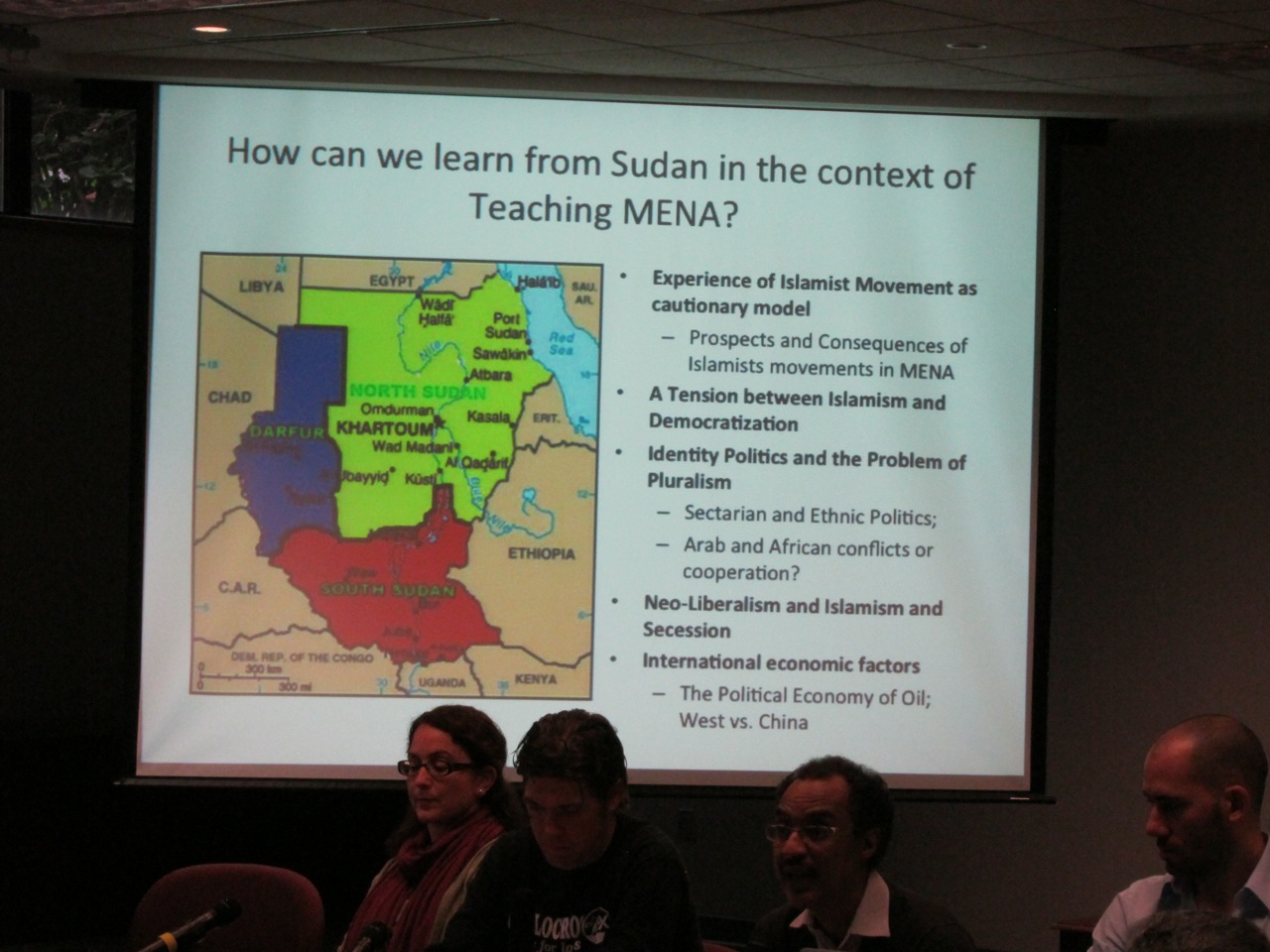

Khalid Medani’s “The Emergence of North and South Sudan: Reinterpreting the Politics of the Nile Valley in the Context of the Arab Revolutionary Movements” highlighted the lessons that could be learned from a deeper understanding and integration of Sudan. For him, Sudan has been anything but peripheral vis-à-vis the question of US interests and intervention (e.g., Darfur). Medani spoke to several areas of inquiry that a deep understanding of Sudan can shed light on: the only Sunni successful Islamist movement to capture the state; political Islam and democratization; identity politics and the problem of pluralism; international economics and the role of Islamic capital.

[Left to right: Linda Herrera, Toby Jones, Khalid Medani, Ziad Abu-Rish, Maya Mikdashi]

Ziad Abu-Rish, in his “Regional Uprisings and Middle East Scholarship: Some Thoughts on What We Can Do Better,” highlighted how disparities in our understanding of the uprisings are reflective of gaps in the available literature on different parts of the Middle East (e.g., Egypt and Tunisia vs. Libya and Yemen). He also discussed the need to move toward a deeper understanding of the variables that inform regime actions (e.g., violence, concessions, cohesion, etc.) in the face of the uprisings as opposed to simply relying on simplistic predictions related to the types of violence a particular leader is perceived to be willing to deploy. Abu-Rish concluded his presentation by stressing the need for historians to pay more attention to the early independence period of Middle Eastern countries and thus have a stake in debates about the legacies of state building and various political/institutional configurations that inform contemporary dynamics.

[Left to right: Toby Jones, Khalid Medani, Ziad Abu-Rish, Maya Mikdashi]

In “Teaching the Middle East After the Revolutions: Critical Perspectives,” Maya Mikdashi focused on what she viewed as the underestimated power of neoliberalism. For her, a focus on the uprisings as simply a reaction to and critique of neoliberalism focuses only the economic aspect of neoliberalism. Mikdashi highlighted the ways that critiques of market-based restructuring of the economy (i.e., appeals to human rights) are themselves implicated in neoliberalism’s role not just as a market-structuring discourse but also a subject forming discourse. In this sense, she is critical of the split in the field of Middle East studies between those that study the economy and those that study the subject, calling instead for a more nuanced and sophisticated analyses.

[Left to right: Ziad Abu-Rish and Maya Mikdashi]

Panel 5: Teaching About Identity and Religion

This panel addressed the challenges and opportunities that the Arab uprisings posed to the teaching of religion and identity in the Arab world. As’ad Abu Khalil began with “Teaching Arab Identity and Islam in Light of the Arab Uprisings,” a presentation that focused on how the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia provided educators with an opportunity to think and teach Arab nationalism and leftist political thought. He pushed participants to think critically about how academia had reproduced the trope that both of these discourses are no longer politically relevant.

[Left to right: As`ad Abu Khalil and Michaelle Browers]

Michaelle Browers, in her “Teaching Political Islam after “Post-Islamism” and the Arab Revolutions,” continued and expanded on this theme, offering examples from her own classroom pedagogy in courses on Arab political thought and Political Islam. She urged educators to pay more attention to the broader history of political thought in the Arab world and political Islam`s place within (not above) it.

[Left to right: As`ad Abu Khalil and Michaelle Browers]

Further challenging the ways in which the politics of the Arab world is conventionally taught, Laurie King’s “Reconsidering Muddles in Middle East Models: the Utility of Ethnography in Pedagogy, Theory-Building, and Public Debate” discussed the importance of using ethnographic texts to expose students to both political discourses and practices. King also discussed how the dominant themes in anthropological writing have yet to be challenged significantly and she questioned anthropology`s recent entanglement with security studies via the Human Terrain Project.

[Left to right: Paul Amar, Laurie King, As`ad Abu Khalil]

Finally, Hayrettin Yücesoy, in his “Revolutions and Teaching the Middle East and Islam,“ concluded the panel with a critical discussion of the ways that the history of the Middle East is over-determined by the history of Islam.

[Left to right on left side of photo: Laurie King, As`ad Abu KHalil, Michaelle Browers, Hayrettin Yucesoy. Left to right on top part of photo: Ziad Abu-Rish, Maya Mikdashi, James Gelvin, Joel Beinin.]

Day 2 Lunchtime Talk by Adel Iskandar

Between the final presentations panel and the first concluding discussion, Adel Iskandar presented a lunchtime talk, "The Arab Media: Unlearning while Teaching on the Arab Media."

[Adel Iskandar]

Closing Discussion 1: Research Agendas

This was the first of two panels intended to gather up the important themes and ideas of the conference and to raise questions and suggestions that would help to set the agenda for future work. This attempt was framed by two questions: How should we distinguish the current discussion from those that the field of Middle East studies seems to have every ten years or so in terms of developing new approaches and responding to current events? What is distinctive about this particular moment, and what are the particular opportunities available to us in formulating research agendas today?

The moderators, Bassam Haddad, Jason Brownlee, and Lisa Hajjar, began by summing up what they saw as some of the major themes raised during the conference: issues of disclosure and conflicts of interest for scholars in the field (with the concrete suggestion that scholars disclose the names of organizations from which they receive honorariums or consulting fees); the question of speaking about power, and to whom (if we want to change U.S. policy towards the Middle East, should our aim be to get heard in the halls of power in Washington, or to direct our voice towards a larger public who would in turn be able to make demands for these changes of policy); and the particular challenges posed by, and to, the field of political science.

Three main clusters of issues were raised for further discussion and as a focus for future research agendas: (1) returning to or revisiting approaches grounded in political economy, as a way to address issues such as neoliberalism, counter-revolution, contentious politics and social movements, and questions related to subjectivity, agency, and institutions; (2) issues of law, war, and revolution, including questions related to human rights, international institutions and enforcement, accountability, police power, state “building” and destroying, and constitutionalism; and (3) major questions regarding how to frame our unit of analysis: should we be satisfied with “the Middle East” as a unit of analysis, as compared to, say, “Arab politics” or “the Islamic world” or other possible categories?

The wider discussion picked up on a number of these themes. There were several comments that addressed the role of the intellectual and the question of who we should be addressing. One interesting conversation involved the question of how power shapes policy: one suggestion was that “power makes people stupid,” and that our role should be to demonstrate that we can make better sense of events on the ground; a contrasting perspective was that those with power are well informed but have different goals and a different sense of what a “rational” foreign policy is, and so our job is to try to push the public discussion rather than try to change the minds of policy makers. It was also suggested that we think about ways of directing our research to colleagues from other disciplines, especially those who may begin teaching issues related to the Middle East in light of recent events.

Another set of discussions was around a recurring theme from the conference: the relationship between approaches grounded in political economy and those grounded in what might be called discourse analysis or issues of representation. There seemed to be a general consensus that a future research agenda should attempt to bring together both approaches and see the value in each, although the consensus also seemed to be that in a lot of recent work, issues of representation had somewhat sidelined political economy (thus the calls for a return to political economy). There was also a call to add the generational dimension, specifically the study of youth and youth culture, to our framework of analysis.

The value of thinking about current events through the framework of “revolution” was also a topic of discussion; one suggestion was that the debate about whether any particular set of events is “really” a revolution or not might be transformed into questions such as where state agents have been replaced by other agents, or how the regime yields to various social forces. There were suggestions that we might look for points of historical comparison (for example, Egypt in 1919), but also cautions about the ways in which misleading historical analogies (the question of whether any particular event is analogous to 1848, 1919, 1946, 1979, etc.) can lead to unproductive frameworks for actually figuring out events on the ground today.

There were several responses to the question of new research opportunities opened up today: for example, it was suggested that this might constitute an important research moment in the sense that new opportunities for data collection may be opened up by the revolutions and uprisings themselves, allowing researchers to depend less on data collected by governments and organizations. Also raised was the possibility of focusing critically on the (misleading) data produced by bodies like the IMF and World Bank as a way to challenge positivist approaches in political science.

Several participants pointed to some of the gaps in the discussions that might be addressed in future conversations and research agendas: for example, there had been little discussion of Tunisia and the role of the Tunisian Revolution; the debates regarding Libya, in particular debates between Libyan scholars and intellectuals and members of the U.S. and European left, had also not been a major focus; and there had not been much discussion of Palestine, leaving open the question of how previous intellectual and political paradigms for thinking about Palestine (such as settler colonialism) might be addressed in our new research agendas.

The panel ended with several questions that may be crucial to setting future research agendas: How do we take account of and address the open-endedness of ongoing events, and the seemingly arbitrary processes that have led to some of these events? In calling for a focus on political economy, are we assuming that the recent uprisings/revolutions have been driven by factors related to political economy, and are we comfortable with this assumption, or is more research needed to determine this? Finally, in making suggestions for our future research agendas, to what extent are we driven by a sense of things that just need to be addressed by the field in a general sense, and to what extent are we driven by the need to find a way of focusing specifically on current and ongoing events in the region—and to what extent do these two needs come together, or not, in the issues we have raised throughout the conference?

[Left to right: Lisa Hajjar, Bassam Haddad, Jason Brownlee]

Closing Discussion 2: Pedagogy and the Classroom

This was the second of two panels intended to gather up the important themes and ideas of the conference and to raise questions and suggestions that would help to set the agenda for future work. The moderators,Pete Moore and Michaelle Browers, began by gathering up what they saw as some of the major themes raised during the conference. These clustered around four main topics: ideas and strategies for moving beyond Orientalism as a way of structuring our pedagogy; evaluating our ongoing and traditional approaches and initiating new approaches; transforming notions of teaching and classroom practice, and re-imaging our roles as educators in light of the recent revolutions and uprisings; and generating new techniques and strategies for the classroom and beyond.

1) Moving Beyond Orientalism: In terms of meeting the conference’s stated goal of moving beyond “defensive” approaches to teaching the Middle East, one set of issues involved trying to think about ways of getting past simply challenging Orientalism, and instead finding more transformative approaches to pedagogy. How, for example, can we find ways of moving beyond simply teaching what the west wishes to know about the Middle East, and move towards teaching about the culture, politics, and communities of the region on their own terms?

2) Approaches Old and New: Moving forward, how can we find institutional spaces and opportunities for introducing new topics and classes, rather than trying to squeeze new approaches into existing curricula or trying endlessly to put new spins on old classes? On the other hand, how can we critically evaluate our pedagogical tools in order to more effectively know what needs to be retained from the past, what needs to be revised and revisited, and what may need to be jettisoned altogether?

3) Transforming Notions of Teaching: What are the roles we wish to play as educators, and how do we determine and establish our pedagogical goals when it comes to teaching the Middle East? How do we adapt our teaching methods in order to better face various forms of institutional challenges: for example, teaching undergraduates within general humanities courses versus teaching specialized graduate courses versus teaching more “professional” oriented courses for students looking to get into politics or diplomacy or intelligence work? How do we formulate our roles as educators in order to better foster future commitments and create new forms of solidarity — in short, in order to be transformative intellectuals?

4) Techniques and Strategies: How do we begin to evaluate our best practices and generate new ideas for bringing the issues discussed at the conference into the classroom? How do we begin to approach the ethical issues raised by new institutional practices — for example, the deeply disturbing ethical issues raised by many study abroad programs set up in the region by U.S. universities? What is the role of the “virtual classroom” — does it really help to link students in different locations, or does it mostly function to indulge certain exoticist curiosities on the part of western students? How can we best use new media technologies and other visual media to meet our pedagogical goals when it comes to teaching the Middle East? How do we address the new forms of campus and classroom politics that will come into existence in the future, and are there opportunities to link these to the political and cultural activities of youth movements in the region?

The discussion that followed picked up on many of these issues. A number of participants talked about the importance of developing strategies for working with new forms of technology, including social media and visual media, in the classroom. The importance of focusing on ethical issues was also a recurring theme: for different participants, this was emphasized as a way for thinking about and dealing with institutional politics, our relationship to students, ways of thinking about the desired “outcome” of our pedagogy, and more generally, the ways in which we as educators could play a part in both introducing students to important analytical frameworks and also playing an active role in transforming the way the region comes to be understood. The importance of addressing these and other issues within graduate programs was emphasized, both because graduate students are grappling with these issues in their own research, and because they are being trained to be the next generation of educators that will be carrying these questions in their classrooms. And, as one participant noted, there was, in light of the changes occurring throughout the region, the need for us all to rethink not just the form of our teaching but also the content of our classes in order to address the new situations that are continuing to emerge.

Conclusion and Moving Forward

The best way to conclude this summary and discussion of “Teaching the Middle East” — indeed, given the structure of the conference and the nature of the conversations, as set out by Bassam Haddad in his opening remarks and reiterated in his remarks before the two closing panels, the only way to conclude — is that the discussions that began at this conference have not yet concluded. Indeed, these discussions are really only getting started. This was part of the conception of the conference itself: as Haddad noted in his opening comments, the idea from the beginning was that it would really be a first step in a longer project aimed at setting new agendas for teaching and research addressing the Middle East, at moving beyond a defensive posture and towards new strategies, and at making sure that the opportunity to make current events part of a teachable moment is actively seized. So by way of a conclusion for now, here are some of the items for these new agendas, as proposed by the conference participants.

In terms of future research agendas, one very fundamental set of questions revolved around the work of the intellectual, whether in the role of educator or scholar (or both at once). The phrase “speaking truth to power” has been used so often that it risks becoming a cliché; a question that became central to the conference was, if our job is indeed to speak truth so as to affect power, to whom should this truth be directed? There was an interesting and productive tension between those who thought that the most productive work might be to find ways to influence policymakers — either directly (by getting ourselves heard in the halls of power) or indirectly (by teaching those who will become the policymakers of tomorrow) — and those who, by way of contrast, suggested that the best aim was to speak truth to a wider public than to “the powerful” more narrowly defined. A related discussion revolved around whether the forms of distortion that have been a part of the dominant discourse on the Middle East are the results of a sheer lack of knowledge (or, as was suggested, the idea that power makes people stupid and leads to a sort of imperial arrogance and ignorance), or whether, on the contrary, these distortions are “rational” in the sense of serving particular interests and agendas. The preliminary discussions around these sets of issues have the potential to influence future conversations about the strategies underlying new sorts of research and pedagogical initiatives.

In a more focused sense, many points discussed during the conference clustered around particular sets of issues that have the potential to influence future research and pedagogical agendas. In terms both of summing up the conference discussions and moving forward with delineating and realizing these agendas, it might be best to break these down schematically:

Research Agendas:

1) Political Economy and Related Approaches: Many of the discussions came back to the importance of revisiting (or, as some participants articulated it, returning to) approaches drawing on political economy. The topics proposed for further investigation through such approaches included:

- Neoliberalism (both as an economic structure but also as a lived reality or life-world)

- Counter-revolution (as it threatens to manifest itself, or has already done so, in many ongoing situations throughout the region)

- Contentious politics and social movements, and their relationship to forms of organized party politics

- Issues related to subjectivity, agency, and institutions

2) Law, War, and Revolution: Another cluster of recurring issues centered around these three topics, especially as related to questions of accountability. Major topics within these categories proposed for further investigation include:

- Human rights

- International law and enforcement

- Accountability

- Police power

- State “building” and destroying

- Constitutionalism

3) Thinking Through Our Units of Analysis: A further set of questions arose regarding the methodological and other sorts of overarching approaches to the issues discussed throughout the conference. Indeed, at the largest level, there was a fruitful set of discussions regarding the very question of how to frame our unit of analysis: Does the rubric of the “Middle East” still provide the most helpful unit of analysis, or do other categories, such as “Arab politics” or “the Islamic world,” hold out the possibility of doing more useful work? Are any of these categories sufficient for our contemporary moment, or do entirely new ones need to be evolved?

Pedagogical Agendas:

1) Moving Beyond Orientalism: In terms of meeting with the conference’s stated goal of moving beyond “defensive” approaches to teaching the Middle East, one set of issues involved trying to think about ways of getting past simply challenging Orientalism and instead finding more transformative approaches to pedagogy. How, for example, can we find ways of moving beyond simply teaching what the west wishes to know about the Middle East, and move towards teaching about the culture, politics, and communities of the region on their own terms?

2) Approaches Old and New: Moving forward, how can we find institutional spaces and opportunities for introducing new topics and classes, rather than trying to squeeze new approaches into existing curricula or trying endlessly to put new spins on old classes? On the other hand, how can we critically evaluate our pedagogical tools in order to more effectively know what needs to be retained from the past, what needs to be revised and revisited, and what may need to be jettisoned altogether?

3) Transforming Notions of Teaching: What are the roles we wish to play as educators, and how do we determine and establish our pedagogical goals when it comes to teaching the Middle East? How do we adapt our teaching methods to face various forms of institutional challenges: for example, teaching undergraduates within general humanities courses versus teaching specialized graduate courses versus teaching more “professional” oriented courses for students looking to get into politics or diplomacy or intelligence work? How do we formulate our roles as educators in order to better foster future commitments and create new forms of solidarity — in short, in order to be transformative intellectuals?

4) Techniques and Strategies: How do we begin to evaluate our best practices and generate new ideas for bringing the issues discussed at the conference into the classroom? How do we begin to approach the ethical issues raised by new institutional practices — for example, the deeply disturbing ethical issues raised by many study abroad programs set up in the region by U.S. universities? What is the role of the “virtual classroom” — does it really help to link students in different locations, or does it mostly function to indulge certain exoticist curiosities on the part of western students? How can we best use new media technologies and other visual media to meet our pedagogical goals when it comes to teaching the Middle East? How do we address the new forms of campus and classroom politics that will emerge, and are there opportunities to link these to the political and cultural activities of youth movements in the region?

As all this suggests, what emerged most clearly by the end of the conference were sets of questions, suggestions, and goals. The work now is to move forward with the inquiries and efforts initiated during these two days.

Once again, we at Jadaliyya, along with Arab Studies Journal, would like to extend our sincere appreciation to the Ali Vurak Ak Center for Global Islamic Studies and the Middle East Program, both at George Mason University, without who`s financial and logistical support, the conference would not have been possible.

PARTICIPANTS AND ABSTRACT TITLES

Producing Knowledge for Justice? Gender and Sexuality Studies and the Consumption of Arabs and Muslims

Rabab Abdulhadi

College of Ethnic Studies, San Francisco State University

Regional Uprisings and Middle East Scholarship: Some Thoughts on What We Can Do Better

Ziad Abu-Rish

Department of History, University of California, Los Angeles

Teaching Arab Identity and Islam in Light of the Arab Uprisings

As’ad Abukhalil

Department of Politics & Public Administration, California State University Stanislaus

Pedagogical Uprisings: Teaching to the Unconverted, or Against Multiculturalism’s Middle East

Tony Alessandrini

Department of English, Kingsborough Community College- City University of New York

How the Egyptian Revolution Teaches Political Sociology, Global Political Economy, Gender Studies, and Geopolitics

Paul Amar

Global & International Studies Program, University of California, Santa Barbara

Rescuing History of Universalism and Modernity from Eurocentric Decline Paradigm

Cemil Aydin

Department of History and Art History, George Mason University

Who’s Afraid of Iran? Neocons’ Enduring Influence on US Policy Analysis

Shiva Balaghi

The Cogut Center for the Humanities, Brown University

Comparative and International Law of the Middle East After the Uprisings: Re-assessing the State of the Arab State

Asli Bali

School of Law, University of California, Los Angeles

Workers and Egypt’s January 25th Revolution: Shifting the Discussion from Autocracy/Democracy to Political Economy and Equity

Joel Beinin

Department of History, Stanford University

Teaching Political Islam after “Post-Islamism” and the Arab Revolutions

Michaelle Browers

Department of Political Science, Wake Forest University

How the January 25th Uprising Is Reshaping the Norms of Egyptian Domestic and Foreign Policy

Jason Brownlee

Department of Government, University of Texas at Austin

Problematics of Teaching International Law in the Contemporary Middle East

Noura Erakat

Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University

Rethinking the Big Picture: Narrating Middle Eastern History in the Wake of the Arab Uprisings, 1944-Present

James Gelvin

Department of History, University of California, Los Angeles

Thoughts Out of Season

Peter Gran

Department of History, Temple University

Prospects for Shifting Strategies: The Production of Knowledge on the Middle East and in the Classroom

Bassam Haddad

Department of Public and International Affairs, George Mason University

Following the Torture Trail From Middle East Studies to American Studies

Lisa Hajjar

Department of Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara

Teaching Islam After the Revolution

Sumaiya Hamdani

Department of History and Art History, George Mason University

Youth and Citizenship in a Digital Age

Linda Herrera

Department of Educational Policy Studies, University of Illinois

Unlearning while Teaching on the Arab Media

Adel Iskandar

Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University

Democracy and Its Limits in the Persian Gulf

Toby Jones

Department of History, Rutgers University

Muddles in the Models: Ethnography and the Mapping of the New Middle East

Laurie King

Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University

Making Connections

Zachary Lockman

Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, New York University

The Emergence of North and South Sudan: Reinterpreting the Politics of the Nile Valley in the Context of the Arab Revolutionary Movements

Khalid Medani

Department of Political Science, McGill University

Teaching the Middle East After the Revolutions: Critical Perspectives

Maya Mikdashi

Department of Anthropology, Colombia University

Back to Basics in Political Economy: Power and Inequality

Pete Moore

Department of Political Science, Case Western Reserve University

De-Orientalizing Pedagogy

Nadine Naber

Women’s Studies, University of Michigan

Teaching Middle East in Theory Courses

Agnieszka Paczynska

Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University

Challenges and Tradeoffs in Moving Beyond Dominant Approaches to the Study of the Comparative Politics of the Middle East

Hesham Sallam

Department of Government, Georgetown University

Disoriented: Rethinking Middle East, Far West, and the Points in Between

Nadya Sbaiti

Department of History, Smith College

Egyptian History Without “Egypt”? Privileging Pluralism in a Post-Revolution Pedagogy

Paul Sedra

Department of History, Simon Fraser University

The Social Relations of Islamophobia and the Role of the Academic

Stephen Sheehi

Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, University of South Carolina

Revolutions and Teaching the Middle East and Islam

Hayrettin Yücesoy

Department of History, Saint Louis University

NON-PRESENTING PARTICIPANTS

Osama Abi-Mershed

Department of History, Georgetown University

Amaney Jamal

Department of Politics, Princeton University

Darryl Li

Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard University

Burhanettin Duran

Department of Political Science and International Relations, Istanbul Sehir University

Kadir Ustun

Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research, Washington DC

Nuh Yilmaz

Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research, Washington DC